Working holidaymakers or backpackers have been in and out of the news throughout 2016, especially in recent weeks. The taxation, exploitation, and economic impact of backpackers has also been the subject of recent senate inquiries and high-level reports. This article seeks to provide an outline of the topic, including relevant statistics, market value and industry influence, controversies, and the impact of offering an extension of the Working Holiday visa for a second year to some applicants.

Index

- Background

- Statistics: Annual working holiday makers

- The value of the backpacker market

- Controversies of the scheme

- Comparison of the scheme to other countries

- Statistics: A breakdown by state

- How the scheme influences other industries and markets

- Impact of the second year visa

- Conclusions

Background

The first Working Holiday Visa program was established in Australia in 1975, and was initially only available to people coming here from the UK and Canada. The program has been expanding ever since, and after the creation of a second subclass of visa in 2005 (the 462 Work and Holiday visa), the program now actively accepts participants from approximately 29 countries. Agreements are underway with a further ten countries including Greece, Hungary, Papua New Guinea and Vietnam, bringing the grand total to 39.

The number of Working Holiday Makers (holders of either a 417 or 462 visa) currently in Australia is estimated at around 240,000. They are joined by students, recent graduates, skilled (417) visa recipients (and less-statistically-visible New Zealanders) to make up the vast majority of Australia’s legal temporary workforce. A recent addition to this temporary workforce is workers from the Pacific who come here via the newly instituted Seasonal Worker Programme, which allows workers from East Timor, Nauru, Kiribati, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu and Vanuatu to work for up to seven months in a 12-month period, for employers in the agricultural industry who have difficulty meeting their seasonal labour needs with local jobseekers.

Statistics: annual take-up of the visa

How many backpackers come to Australia each year on a working holiday visa? Here’s a breakdown of the annual take-up of the visa; for each year that statistics are available.

Some key stats

Current numbers of temporary work visa holders (as of September 2015)

- 299,540 – Student (500) visa holders (allowed to work up to 40 hours per fortnight for the duration of their studies)

- 22,895 – Temporary graduate (485) visa holders (allowed to work for between 18 months and four years after completing their studies here in Australia)

- 200,000 – This is a key growth area according to CEDA, who predict up to 200,000 applicants for the 2017-2018 financial year

- 85,611 – Skilled (457) visa holders in the 2015-2016 financial year

- $53,900 – Minimum wage threshold for 457 applicants

- 239,592 – Total Working Holiday Maker (417 and 462) visas issued in the 2013-2014 financial year

- 214,830 – Working Holiday (417) visas issued in 2014-15

- 11,982 – Work and Holiday (462) visas issued in 2014-15

- 7% – The percentage of Australia’s workforce that is working under a temporary work visa

Sources: Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA), Migration: the economic debate (November 2016), Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Working Holiday Maker program reports, (various years) via the parliamentary Guide to Working Holiday Makers in Australia.

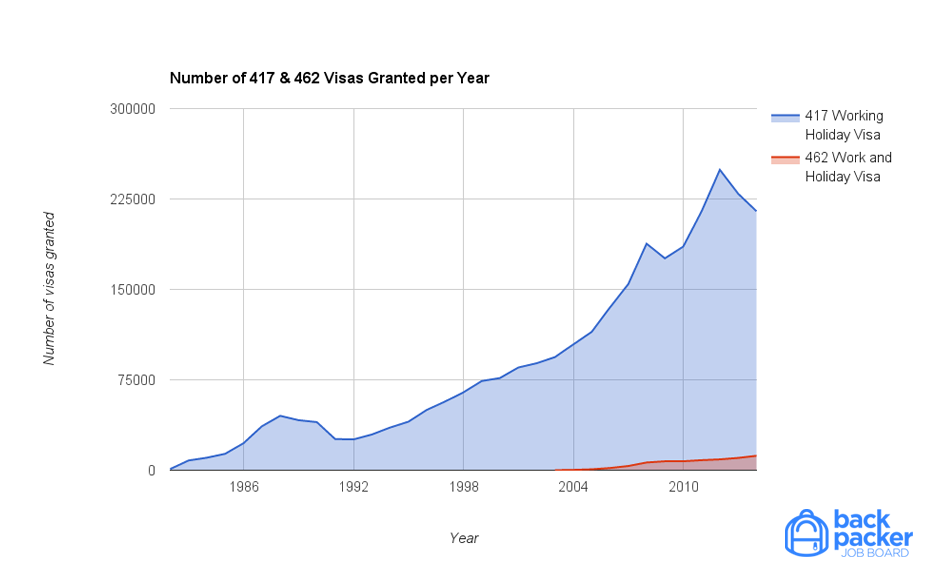

Number of Visas granted per year

The following statistics are taken from the Guide to Working Holiday Makers in Australia. © Commonwealth of Australia (creative commons).

Table 1: Working Holiday (subclass 417) visa grants, 1982–83 to 2003–04

| Year | Visas Granted |

|---|---|

| 1982 – 1983 | 979 |

| 1983 – 1984 | 8,096 |

| 1984 – 1985 | 10,400 |

| 1985 – 1986 | 13,622 |

| 1986 – 1987 | 22,413 |

| 1987 – 1987 | 36,428 |

| 1988 – 1989 | 45,136 |

| 1989 – 1990 | 41,538 |

| 1990 – 1991 | 39,923 |

| 1991 – 1992 | 25,873 |

| 1992 – 1993 | 25,557 |

| 1993 – 1994 | 29,595 |

| 1994 – 1995 | 35,391 |

| 1995 – 1996 | 40,273 |

| 1996 – 1997 | 50,000 |

| 1997 – 1998 | 57,000 |

| 1998 – 1999 | 64,550 |

| 1999 – 2000 | 74,000 |

| 2000 – 2001 | 76,500 |

| 2001 – 2002 | 85,207 |

| 2002 – 2003 | 88,758 |

| 2003 – 2004 | 93,845 |

Sources: Immigration Department (there have been many departmental name changes over the years), annual reports, (various years); Joint Standing Committee on Migration, Working Holiday Makers: more than tourists, Canberra, August 1997, p. 19.

Table 2: Working Holiday (subclass 417) and Work and Holiday (subclass 462) visa grants, 2003–04 to 2014–15

Table 2 shows the continuation of visa grants allowing for the introduction of the 462 visa.

| Year | Working Holiday Visa (417) | Work and Holiday Visa (462) |

|---|---|---|

| 2003 – 2004 | 93,845 | 23 |

| 2004 – 2005 | 104,353 | 257 |

| 2005 – 2006 | 114,693 | 751 |

| 2006 – 2007 | 134,993 | 1,812 |

| 2007 – 2008 | 154,342 | 3,488 |

| 2008 – 2009 | 187,907 | 6,409 |

| 2009 – 2010 | 175,746 | 7,422 |

| 2010 – 2011 | 185,480 | 7,442 |

| 2011 – 2012 | 214,644 | 8,348 |

| 2012 – 2013 | 249,231 | 9,017 |

| 2013 – 2014 | 229,378 | 10,214 |

| 2014 – 2015 | 214,830 | 11,982 |

Sources: 2003–04 to 2004–05: Immigration Department, annual reports; 2005–06 to 2014–15: Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Working Holiday Maker program reports, (various years).

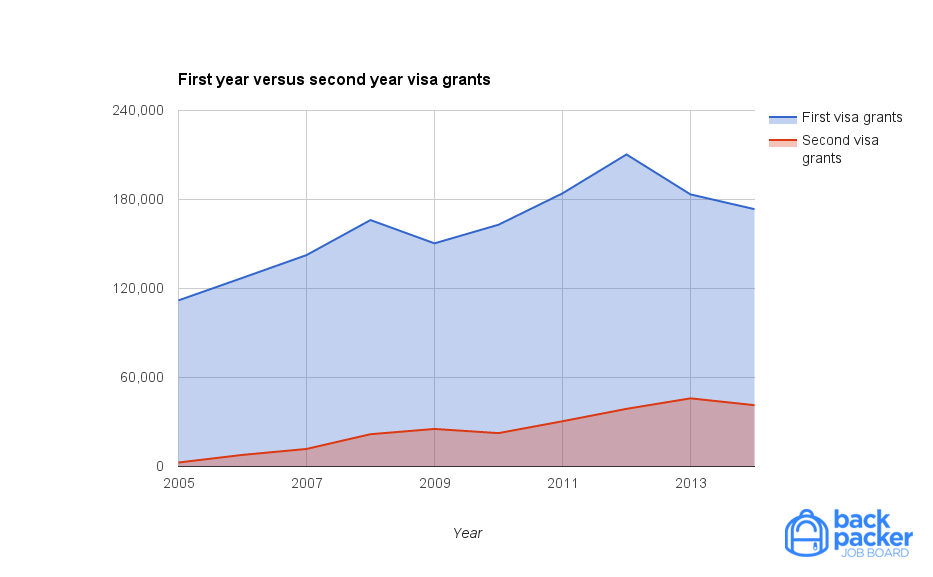

Table 3: Working Holiday (subclass 417), second year visa take-ups

What percentage of backpackers complete the second year visa?

| Year | First visa grants | Second visa grants | Percentage take-up |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 – 2006 | 111,996 | 2,690 | 2.40% |

| 2006 – 2007 | 127,171 | 7,822 | 6.15% |

| 2007 – 2008 | 142,516 | 11,826 | 8.30% |

| 2008 – 2009 | 166,132 | 21,775 | 13.11% |

| 2009 – 2010 | 150,431 | 25,315 | 16.83% |

| 2010 – 2011 | 162,980 | 22,500 | 13.81% |

| 2011 – 2012 | 184,143 | 30,501 | 16.56% |

| 2012 – 2013 | 210,369 | 38,862 | 18.47% |

| 2013 – 2014 | 183,428 | 45,950 | 25.05% |

| 2014 – 2015 | 173,491 | 41,339 | 23.83% |

Notes: visa recipients do not necessarily arrive in Australia in the same program year that the visa is issued; second visas may not be granted to recipients in the same year as the first visa grant; the option of a second Working Holiday visa was introduced on 1 November 2005.

Sources: 2005–06: Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee, Answers to Questions on Notice, Immigration and Citizenship Portfolio, Supplementary Budget Estimates 2010–11, Question 192, 19 October 2010; 2006–07 to 2014–15: Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Working Holiday Maker visa program reports, (various years).

The value of the backpacker market for Australia

Direct economic benefits:

- Money spent by backpackers

- Tax revenue on the income of backpackers

- Tax revenue on superannuation paid to backpackers

Indirect economic benefits:

- Backpackers support businesses, particularly agricultural businesses, by supplying a demand for skilled seasonal labour

- Backpackers enrich the multicultural experience of regional communities

- Indirectly, the existence and continued strength of the working holiday market in Australia provides many benefits to Australia’s economy. The strength and increased numbers of reciprocal working holiday agreements means that young (18-30yo) Australians have the opportunity to travel to participant countries, gaining many specific skills which transfer in beneficial ways to the Australian labour market.

Each backpacker spends an average of $5,294 in Australia, $3209 of this in rural areas (sourced from the International Visitor Survey results from March 2015). The value of backpackers to the Australian economy is therefore in the order of 240,000 x $5,294 or $1.3 billion, with $770M being spent in rural communities. ‘The more time they spend in rural and regional areas,’ argues Traci Wilson-Brown of WWOOF Australia, ‘the more these economies are stimulated, helping support the tenuous job situations in Regional Australia.’

It is worth noting that the economic and workforce benefits of the Working Holiday visa market are particularly felt in regional and rural communities, which makes those benefits especially valuable, as indicated by the many incentives introduced since 2005 to encourage backpackers to work in regional Australia, especially the Northern Territory and far north Queensland.

Are backpackers taking or creating jobs?

Writing about the volunteer workers who account for as many as 12,000 temporary work visa holders, Wilson-Brown argues: ‘Each farm that remains viable because of the help they get from their WWOOFers means money from these farms and their families stays in the rural economy, their children stay in local school and flow on jobs are also connected to this.’

An Evaluation of Australia’s Working Holiday Maker Program, conducted in 2009 by the then Department of Immigration and Citizenship, the gross economic contribution of the total 134,388 backpackers in Australia in 2007-8 was estimated at $1.8 billion.

‘The study identified that backpackers are actually positive for domestic employment, with every 100 WHV holder generating 6.3 full time jobs for Australians,’ said Dr Jeff Jarvis, director of the Graduate Tourism Program at Monash University.

A pathway to permanent migration?

Approximately 190,000 people are granted permanent residency in Australia every year, and as many as 50 per cent of applicants accepted come from the ‘existing pool of temporary visa-holders.’ Emigration means that the net migration into Australia each year is lower- the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) recorded that net migration into Australia for the 2014-2015 year was 168,200 people.

Although recent studies have shown that although the average stay of a working backpacker is only eight months, Janet Phillips suggests that the program can and is used by some participants as a pathway to longer stays (including permanent residency) through application for other visas such as the (subclass 457) skilled worker visa. However, this suggestion seems to rest on evidence that an increasing number of 457 applications are coming from people already in the country, including those currently holding student and other temporary visas.

There are significant measures in place to ensure that migrant workers visiting Australia are skilled, and evidence suggests that an intake of young, skilled temporary migrants is beneficial for the national economy. Visitors accepted through the Work and Holiday (subclass 462) visa must be aged 18-30, be proficient in the English language, have at least two years of undergraduate qualification (excepting residents of Israel and the US), and (excepting residents of China, Israel, and the US) have a letter of support from their government.

A recent report on the economic impact of migration in Australia has confirmed that immigration into Australia has significant regional and national economic benefits, and that this is especially this case since 1997-98 when Australian immigration policy began to deliberately favour skilled workers over other types of visa applicants. In the 80s, around 30 per cent of all Australian migrants were skilled. These days, that figure is much higher, and currently hovers around 70 per cent.

Controversies of the scheme

Exploitation of Backpackers

More than one tenth of all complaints received in 2013-2014 by the Fair Work Ombudsman (FWO) were from temporary work visa holders. Many of these were high-profile cases that exposed how temporary workers, among them backpackers, are being exploited.

Research collated by the Fair Work Ombudsman and conducted as part of the Senate inquiry notes ‘numerous examples over time of exploitation of temporary migrants on temporary student, skilled work, working holiday or Pacific Seasonal Worker visas. Examples of co-ethnic exploitation are also common.’

The final inquiry report notes that exploited temporary work visa holders tend to be young, face language barriers, and be less aware of their employment rights. They also tend to work in low or semi-skilled jobs, meaning ‘they have less ability to resist the coercive behaviour of unscrupulous employers’ as well as less access to ‘social or economic support networks able to counter the market powers of their employers.’ The requirement to work for at least three months in a qualifying agricultural or other ‘high demand industry’ job before 417 visa holders can apply for a second year must also place pressure on some workers who are seeking to qualify in a short timeframe and can’t afford to stop and find alternative work.

Exploitation by employers, aside from the considerable immediate damage it does to the employee, has two further and far-reaching damaging effects: it undermines Australian employers who are providing fair pay and work conditions; and it jeopardises future migrant flows into agricultural jobs. As Wilson-Brown (of WWOOF Australia) points out, backpackers who have positive experiences while working in Australia’s agricultural industry become ‘[unwitting or deliberate] ambassadors for this country.’ The inverse of this is also true- the stories of workers who are exploited and mistreated act as deterrents for Australia’s temporary work visa programs, undermining recent awkward efforts to attract new entrants to the scheme.

Backpacker Tax on Superannuation

Grower representative associations like AUSVEG argue that proposed changes to backpacker tax system will be a disincentive for new backpackers to apply. In defence of these measures, then Treasurer Scott Morrison argued that candidate backpackers will not be attracted away to comparable destinations because of our relatively high minimum wage. Judith Sloan for The Australian newspaper argues that the Treasure is ‘more than happy to impose high costs on employers that typically rely on Working Holiday Maker visa holders… the absurd expropriation by the government of the superannuation contributions made on behalf of this group should be scrapped immediately.’

At the time of writing, overseas workers must be paid a minimum 9.5 per cent of their wages in super if they:

- Earn over $450 in a month from that employer,

- and are over 18

It does not matter if the worker is employed on a permanent or casual basis, or if the worker is considered a resident or non-resident for tax purposes. Employers must pay superannuation for workers if they meet the above criteria.

The superannuation paid by the employer is taxed at 15 per cent by the ATO. Backpackers and students are allowed to withdraw their superannuation if they permanently leave Australia and their visa expires. The Australian government takes out further 35 per cent tax when you apply for the withdrawal.

From the 1st of January 2017, backpackers will be taxed 95c in the dollar. It’s not yet clear whether or not they will be charged a further 35 per cent on what remains when they withdraw.

Volunteering

Volunteering: no longer an option for the three months of ‘specified work,’ despite pleas from regional agricultural employers desperate for the help.

During National Volunteer Week last year, Minister for Border Protection and Immigration Peter Dutton announced that backpackers (holding the subclass 417 visa) would no longer be able to count time spent volunteering towards the three months of ‘specified work’ that must be carried out in order to get their 417 visas extended for a second year.

WWOOF Australia, the local organization of an international movement that promotes Willing Workers on Organic Farms, was justifiably flabbergasted. They outlined the issue in a letter to Minister Dutton as well as a paper submitted to the Senate’s inquiry into the impact of Australia’s temporary work visa programs on the Australian labour market and on the temporary work visa holders.

‘Working Holiday Visa holder numbers are down 5.8% in 2014 on the 2013 year and WWOOFer numbers have fallen too,’ says Traci Wilson-Brown of WWOOF Australia. ‘We are concerned this change will significantly diminish WWOOFer numbers further leaving many hosts struggling to keep their farms going. Without the enticement of the visa extension many will not join WWOOF.’

Working Holiday visa extensions were implemented in order to encourage backpackers to work in regional areas doing seasonal work. This is physically demanding and often difficult for young backpackers from city backgrounds, whom the paper points out ‘have rarely driven a tractor, erected a fence or picked an apple and have few, if any farming skills.’ ‘Real farmers need skilled workers if they are paying award wages,’ the report continues ‘and volunteering offers the opportunity to gain these skills.’

The report also makes clear the value of the Australian Organic industry to the economy and labour market: the Australian organic market is currently valued at $1.72B and is the fastest growing agricultural industry. ‘WWOOFing provides an opportunity for small scale organic farming operations to start up. It assists those businesses with annual sales under $40,000 and does this without any financial assistance from the government.’

Impact on regional youth unemployment

Evidence on the domestic labour impact of backpackers is mixed. In general, research shows a positive impact on the economy as well as direct job creation. The strongest case for a negative impact on the labour market appears when we look at low-skilled unemployed youth.

A 2009 study on the effects of WHVs on domestic youth unemployment specifically commented that: ‘it is still possible that on balance [backpackers] reduce the job opportunities for Australians in local labour markets. We do not have direct evidence on this point. We do know that backpackers overwhelmingly work in relatively unskilled jobs that most Australians could do.’ It’s worth noting as well that while temporary migrants accounted for just 4.2 per cent of the workforce for the general civilian population (in 2009), they made up 17.9 per cent of the workforce for the 20–24 age bracket.

Some mitigating facts: As we’ve seen, working holiday visa holders account for less than a third of all temporary workers in Australia, excluding New Zealanders. It’s also unfair on Australian workers to talk about seasonal jobs – harvest work that might exist for as little as a few months or weeks a year – as though they are jobs being taken out of the hands of domestic workers. If there is an unemployed workforce in a region that can benefit from one or two months of paid seasonal work, what are they doing for the rest of the year? It’s reasonable to assume that they are seeking permanent full or part-time positions, and that their permanent employers will not gladly give them months of leave to work these seasonal jobs.

It is true that unemployment figures for school leavers aged 15-19, as well as graduates aged 20-24, remain stubbornly high. Recent (2015) research by the Australian Productivity Commission shows a correlation between higher numbers of migrant workers and increased youth unemployment among Australian-born and naturalized Australian citizens. But as CEDA points out, it’s difficult to say whether this correlation is ‘simply a product of broader shifts in the labour market, or whether temporary migration, at least in part, is displacing low-skilled workers…and competing for graduate positions.’ CEDA expects the graduate visa category, with over 22,000 visas issued last year, to grow considerably to some 200,000 applications for the year 2017-2018. If this prediction proves valid, the pressure on the graduate labour market from foreign-educated backpackers will pale in comparison to the pressure from recent graduates from domestic universities.

The last exhaustive study undertaken on the regional labour market effects of WHVs was carried out in 2001, when the number of backpackers was significantly smaller, and the national and global employment patterns rather different. That study found that the effect of backpackers on local unemployed youth was negligible for many reasons, but the data and conclusions are now out of date, and some of the parameters have changed too (for example backpackers can now stay with the same employer for twelve months).

The recent CEDA report on migration argues that research into the effects of temporary workers on the domestic labour market have so far adopted a national approach, while research still needs to be done to assess the regional effects of migration on the labour market, especially ‘with regards to youth unemployment, where there is strong regional variation in unemployment rates across Australia.’ Harding and Webster’s 2001 research found that only a fraction of the jobs occupied by backpackers would otherwise have been occupied by local unemployed youth, noting that comparable positions occupied by domestic workers were much more likely to be filled by full-time students or mature women. However, as we’ve already seen, that report is now out of date, and new data needs to be collected.

Conflation of controversial issues, facts and figures with 457 visa

There are significant concerns about the way in which 457 temporary working visas are granted, voiced by the general community, by industry, and by independent commissions. These concerns mostly centre on the de-facto powers of the private sector to determine and regulate ‘demand’ levels in different professions and industries. This should not be confused with the issues and challenges affecting the Working Holiday and Work and Holiday market, which is regulated significantly more strenuously and in a way that strategically responds to real needs in the Australian job market. But it’s likely that in public discourse the issues (as well as the facts and figures) relating to the 457 visa market are being conflated with the concerns, facts and figures around the WHV.

Comparison of the WHV scheme to other countries

Australia is considered to have a world-leading Working Holiday Maker program, but recent legislation changes affecting WHVs and flow-on controversies, doubt and negative press result in a need at present to re-establish the reputation of the program as one of the best.

There is a danger that attempts by the federal government to increase the amount of direct revenue taken from backpackers, as well as an attempt to mitigate community concerns about regional youth unemployment by placing arbitrary limits on temporary transient workers, could function as disincentives to prospective backpackers. Minister for Health, Sussan Ley, argued on ABCs Q&A programme (31 Oct 2016) that even with a 19 per cent income tax and a 95 per cent superannuation tax, “there is competitiveness between Canada, New Zealand, UK and other places,” presumably based on Australia’s relatively high wages.

The Australian Working Holiday scheme has also recently been compared to other nation’s Working Holiday programs with respect to capping the numbers of visas granted each year.

Capping the scheme

The CEDA report, Migration: the economic debate (November 2016), recommends several times that capping the number of working holiday visas issued should be considered, citing the parliamentary report A National Disgrace: The Exploitation of Temporary Work Visa Holders (17 March 2016). That report also only recommends that a cap be considered, without suggesting numbers or mechanisms for determining numbers. The latter report also clearly recommends capping other forms of temporary working visas, particularly the international student 485 and 457 visas.

By way of trying to find out what a future cap on the Working Holiday (417) visa program might look like, I’ve done some research into Canada’s program. What number does Canada cap their intake at, and by what mechanism? The number in 2016 was a total of 95,648. This was made up of separate caps for each country in the International Experience Canada (IEC) program, and the IEC state that caps can increase based on higher numbers of applications. However, once caps are decided upon for a certain region in a given year, they are enforced, and in 2012 and 2013 the IEC filled its quota for applicants from the UK and Ireland in record time. National caps applied to at least 28 eligible countries and ranged from 92 (for Latvia) up to 16,254 (for Australia).

In fact, the Australian WHV program is already affected to an extent by two existing caps: firstly, no new countries have been added to the 417 visa program since 2006. All agreements entered into in the last decade have been through the subclass 462 Work and Holiday agreements, which have, according to the parliamentary Guide on the subject ‘more restrictive requirements (including visa caps).’

Secondly, all Work and Holiday visa signatory countries (excluding the USA) have caps on the number of visas available per year under this program (a full list of the different visa caps are provided in departmental WHV reports). The respective caps for partner countries are:

- USA: no cap (commenced 2007)

- China: 5,000 (commenced 2015)

- Chile: 1,500 (commenced 2006)

- Indonesia: 1,000 (commenced 2009)

- Argentina: 700 (commenced 2012)

- Thailand, Greece, Israel, Spain: 500

- Uruguay, Poland, Portugal, Vietnam, Slovak Republic, Slovenia: 200

- Bangladesh, PNG, Malaysia, Turkey: 100

Source: Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Working Holiday Maker visa program reports, (various years) via the parliamentary Guide to Working holiday Makers.

Statistics by state

Government-held data exists to show where backpackers spend some of their time, as captured via their employers. Similarly, Working Holiday (417) visa holders who are applying for a second 417 visa must prove that they have worked for at least three months (or 88 days) in ‘specified work,’ and the data used to prove that should give the government useful data on where backpackers are working in general and especially where this ‘specified work’ is taking place.

It may be worth pointing out here that it’s reasonable to assume that many temporary work visa holders engage in ‘under the table’ work that is invisible to researchers and data collectors. It is safe to assume that Working Holiday visa holders -as well as those on other travel, study and other temporary work visas- enter into agreements for ‘under the table’ work, since there are significant pressures that could potentially make this option attractive to both employees and their employers. It should not, however, be assumed that these agreements are entered into at the suggestion of backpackers, or even with the informed consent of those workers. The rate of exploitation of temporary work visa holders in Australia is so high that officials have deemed it ‘a national disgrace.’ Temporary international workers are often understandably unclear on how employers are expected to fulfil their legal requirements in terms of staffing hours and conditions, wages and tax payments.

Despite the fact that federally-collected data should provide some useful state by state statistics on backpacker employment and stay, this breakdown of data is not readily available.

Is there any relevant state-by-state data?

Yes. Significantly, overall visitor numbers and visitor spend are up in every state and territory except the Northern Territory (which fell between June 2015 and June 2016, according to Tourism Research Australia). This data echoes the recent white paper on Northern Australia, including the changes made to allow backpackers to extend their length of employment in certain types of work there.

Influence of the scheme on industries

There’s clear evidence that the scheme benefits the tourism and agriculture industries. For example, any Working Holiday (417) visa holder can now qualify for a second year’s 417 visa by working in any sector of agriculture or tourism, so long as that work happens in Northern Australia. From November 21, 2015, both Working Holiday (Subclass 417) and Work and Holiday (Subclass 462) visa holders have been able to apply to work for a single employer for up to 12 months, if they can secure work in certain ‘high demand industries’ across Australia’s underserved North.

Tourism and hospitality

The impact on the tourism industry is twofold: on the one hand, the scheme allows up to 240,000 tourists to visit Australia who would not otherwise choose to visit. While most of these visitors earn money while they’re here, the majority of that money stays in Australia, and many backpackers supplement their tourism spending with money brought in from abroad.

On the other hand, these workers provide seasonal staff – both unskilled and highly qualified – to areas of tourism that rely on higher numbers of employees than can be reliably provided by the local workforce. The expansion of the working holiday extension qualification categories to include tourism in Northern Australia shows that the government hopes this supplementary, temporary workforce can be used to grow the tourism and hospitality industries across Northern Australia.

Aged care and disability services

The changes made in November 2015 also allowed both subclasses of Working Holiday visa holders to remain with the same employer for a total of twelve months instead of six if they work in disability or aged care services, an industry chronically underserved by the local Australian-born workforce. Minister for Border Protection and Immigration Peter Dutton said these changes would make it easier for Working Holiday makers to ‘help to unlock the immense potential of Australia’s north and help facilitate strong economic growth.’

Agriculture

Immigrant workers (both permanent and temporary) contribute significantly to the productivity of the Australian agricultural industry, a new report reveals. Backpackers fill crucial farm jobs and fruit picking jobs during the peak picking and harvesting seasons.

Representative organisations from the wine, dairy, pork, beef and organic growing markets made submissions in response to the 2015 senate inquiry into the impact of the temporary worker program, showing that any potential reduction in the 240,000-odd annual supply of seasonal workers would be widely felt.

In May 2016, leading vegetable industry body AUSVEG expressed its disappointment at the lack of action taken by the Federal Government to change or eliminate the backpacker tax. Growers are concerned that the proposed tax changes, which will remove the tax-free threshold and increase the amount of tax paid by workers who come to Australia under the WHV program, will act as a deterrent to work on Australian farms and jeopardise the viability of the vegetable industry.

‘While Australian growers’ first preference is always to employ local workers, there is simply not enough local labour to satisfy demand during peak harvesting periods, and backpackers play a vital role on Australian farms by providing a workforce during these critical times,’ said AUSVEG Deputy CEO Andrew White.

‘The ongoing decline in backpackers visiting Australia must be arrested if the Australian vegetable industry is to remain viable. Any further decrease in the number of backpackers visiting Australia due to the tax could have a crippling impact on the Australian vegetable industry, threatening the future productivity and profitability of our growers.’

Impact of the second year visa

The second Working Holiday visa is valid for a further 12 months. First-time Working Holiday (subclass 417) visa holders who do three months (88 days) of ‘specified work’ (eligible second year visa jobs) in regional Australia during their stay acquire eligibility to apply for a second such visa. This work includes work in the agriculture, mining and construction industries. The term ‘regional Australia’ applies here to large areas of rural and regional Australia and is officially defined for the purposes of second Working Holiday visa eligibility by a list of postcodes.

Impact

The second year Working Holiday provides a powerful incentive for workers already in Australia to add their labour to the Australian job market where it is most necessary, namely in the specified industries and regional areas. With roughly a 25 per cent uptake of the second year visa by first-year holders, we can say that the offer is well received among backpackers. Furthermore, with second-year visa recipients reaching over 41,000 in 2014-2015, we can say that over 41,000 jobs were filled for at least three months of last year.

Statistics

The number of second Working Holiday visa grants has grown rapidly since the program commenced in November 2005. Second year visas now constitute 19.2 per cent of the overall Working Holiday visa grants in 2015-2016, up from a 3.3 per cent share the first year after the second year option was introduced.

There is no cap on the number of first or second year Working Holiday visas issued, and the number of second-year grants has increased substantially (from just over 2,690 in 2005–06 to 41,339 in 2014–15) since the option of a second working holiday visa was introduced. It should be noted, however, that while the number of grants of Work and Holiday (subclass 462) visas are going up exponentially, bolstered by the ongoing addition of new partner countries, the number of Working Holiday (subclass 417) visa applicants has actually been decreasing since 2013, and the numbers of second-year applications has been decreasing as well.

Statistics on employer industry are not available for first visa grants under the WHV program, but they are available for the second Working Holiday visa grant. Since its introduction in 2005 the vast majority of second visas have been granted to those employed in agriculture (about 93 per cent), with the remaining in construction (about six per cent) or mining work (about one per cent).

Conclusions

WWOOF Australia submitted a petition of just over 5000 signatures to Senator the Hon Michaelia Cash (then the Assistant Minister for Immigration and Border Protection) and Minister Dutton, requesting that the government ‘include volunteer work activities, such as Willing Workers on Organic Farms (WWOOF), in the eligibility framework for the second Working Holiday (subclass 417) visa.’ As of November 7, 2016, there is still no update, and volunteer work remains removed from the eligibility framework since late 2015.

Further research is needed to outline several key aspects of the actual activities, rather than the official figures and legislation, of Working Holiday Visa holders in Australia, and to outline the possible implications of these activities. For example, 41,399 successful second-year 417 visas issued in 2014-2015 can be said, fairly reliably, to indicate that at least 41,399 backpackers worked for at least three months in specified work. But we need to know more.

Do backpackers tend to work in these critical job roles in ‘high demand’ industries and regions for longer than the three months required? Do backpackers who hold work visas spend more tourism dollars during their travels in Australia than those who don’t? What percentage of successful organic farming businesses have relied in the past on volunteers to incubate their early growth phase? What percentage of temporary work visa holders are actually paid superannuation at present? And how many of them actually ever collect it? Harding and Webster’s 2001 research is a good example of the questions that need to be asked, but that work is now out of date.

References

- 1 http://www.australiaforum.com/information/jobs/immigration-is-crucial-to-australias-wellbeing-but-impact-needs-more-research.html (published Oct 25, 2016; retrieved November 4, 2016)

- 2 http://www.aph.gov.au/DocumentStore.ashx?id=79393b8a-4334-4954-96ba-9ecd20847353 (published November 20, 2015; retrieved November 7, 2016)

- 3 http://www.thebyte.com.au/whv-taking-creating-australian-jobs/

- 4 http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/02/opinion/powering-australias-economic-surge.html (published November 1, 2016; retrieved November 4, 2016)

- 5 https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2016/nov/03/australia-could-double-annual-migration- by-2054-and-boost-economy-report (published November 3, 2016; retrieved November 4, 2016)

- 6 http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/02/opinion/powering-australias-economic-surge.html?_r=0 (published November 1, 2016; retrieved November 4, 2016)

- 7 Ed. Joanna Howe and Rosemary Owens, Temporary Labour Migration in the Global Era: The Regulatory Challenges. Bloomsbury, Portland: 2016.

- 8 http://adminpanel.ceda.com.au/FOLDERS/Service/Files/Documents/32509~CEDAMigrationReportN ovember2016Final.pdf (p9, published November 1, 2016; retrieved November 4, 2016)

- 9 https://theconversation.com/how-migrant-workers-are-critical-to-the-future-of-australias-agricultural-industry-66422 (written by Jock Collins; published October 12, 2016; retrieved November 7, 2016)

- 10 https://theconversation.com/how-migrant-workers-are-critical-to-the-future-of-australias-agricultural-industry-66422 (written by Jock Collins; published October 12, 2016; retrieved November 7, 2016)

- 11 http://www.workstay.com.au/superannuation-oversea-workers-australia

- 12 http://www.aph.gov.au/DocumentStore.ashx?id=79393b8a-4334-4954-96ba-9ecd20847353 (published November 20, 2015; retrieved November 7, 2016)

- 13 http://www.aph.gov.au/DocumentStore.ashx?id=79393b8a-4334-4954-96ba-9ecd20847353 (published November 20, 2015; retrieved November 7, 2016)

- 14 Tan et al, 2009, op.cit, note 23, page 57; via CEDA, Migration: the economic debate (p49 published November 2016, retrieved November 4, 2016)

- 15 Cully 2010, op.cit, note 24, page 2. Note, the Productivity Commission (2016) Inquiry Report: Migrant Intake into Australia, Productivity Commission, Canberra, estimates the figure at 13.7 per cent: page 201 via CEDA, Migration: the economic debate (p49 published November 2016, retrieved November 4, 2016)

- 16 Productivity Commission, 2015, op.cit, note 12, Figure 15.5d-f via CEDA, Migration: the economic debate (p49 published November 2016, retrieved November 4, 2016)

- 17 CEDA, Migration: the economic debate http://apo.org.au/files/Resource/32509_cedamigrationreportnovember2016final.pdf (p49 published November 2016, retrieved November 4, 2016)

- 18 CEDA, Migration: the economic debate http://apo.org.au/files/Resource/32509_cedamigrationreportnovember2016final.pdf (p4,9,51-52, published November 1, 2016; retrieved November 4, 2016)

- 19 http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Education_and_Employment/temporary_work_visa/Report

- 20 https://workingholidaystore.com/international-experience-canada-open/

- 21 http://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1516/Quick_Guides/WorkingHoliday#_Table_4:_Working

- 22 http://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1516/Quick_Guides/WorkingHoliday

- 23 http://www.minister.border.gov.au/peterdutton/2015/Pages/visa-changes-to-benefit-northern-economy.aspx

- 24 http://www.ausveg.com.au/media-release/lack-of-action-on-backpacker-tax-in-federal-budget-will-hurt-aussie-growers

- 25 http://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1516/Quick_Guides/WorkingHoliday

- 26 http://www.border.gov.au/ReportsandPublications/Documents/statistics/working-holiday-report-jun16.pdf

- 27 Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Working Holiday Maker visa program reports, via the parliamentary Guide to Working Holiday Maker visas